[00:00] (0.00s)

- This is a microchip.

[00:01] (1.52s)

When you zoom in, you find

a nanoscopic computing city

[00:05] (5.04s)

skyscrapers, hundreds of

layers tall with hundreds

[00:08] (8.08s)

of kilometers of wires

connecting everything.

[00:10] (10.88s)

And at the very bottom, is this

[00:13] (13.92s)

transistors, billions of them.

[00:17] (17.44s)

They are the ones and

zeros of our computer.

[00:20] (20.40s)

The chip works by whizzing

electrons from transistor

[00:22] (22.72s)

to transistor, and the

smaller you can make those

[00:25] (25.20s)

transistors, the less the

signals have to travel,

[00:27] (27.44s)

so the faster they can compute.

[00:29] (29.36s)

Plus you can fit more

transistors into the same area,

[00:32] (32.56s)

resulting in a much more powerful chip.

[00:35] (35.44s)

So for over 50 years, transistors

got smaller and smaller,

[00:38] (38.96s)

and the number you could

fit on a chip doubled

[00:41] (41.20s)

every two years.

[00:42] (42.72s)

This became known as Moore's Law named

[00:44] (44.88s)

for Intel's co-founder Gordon Moore,

[00:46] (46.88s)

after he noticed the pattern back in 1965,

[00:49] (49.44s)

and it's been one of the main

drivers of the tech industry.

[00:52] (52.64s)

But around 2015, progress

came to a screeching halt,

[00:56] (56.40s)

and we might have never

gotten past it if it wasn't

[00:58] (58.96s)

for a single company that makes

these machines, the machines

[01:03] (63.20s)

that saved Moore's Law.

[01:04] (64.96s)

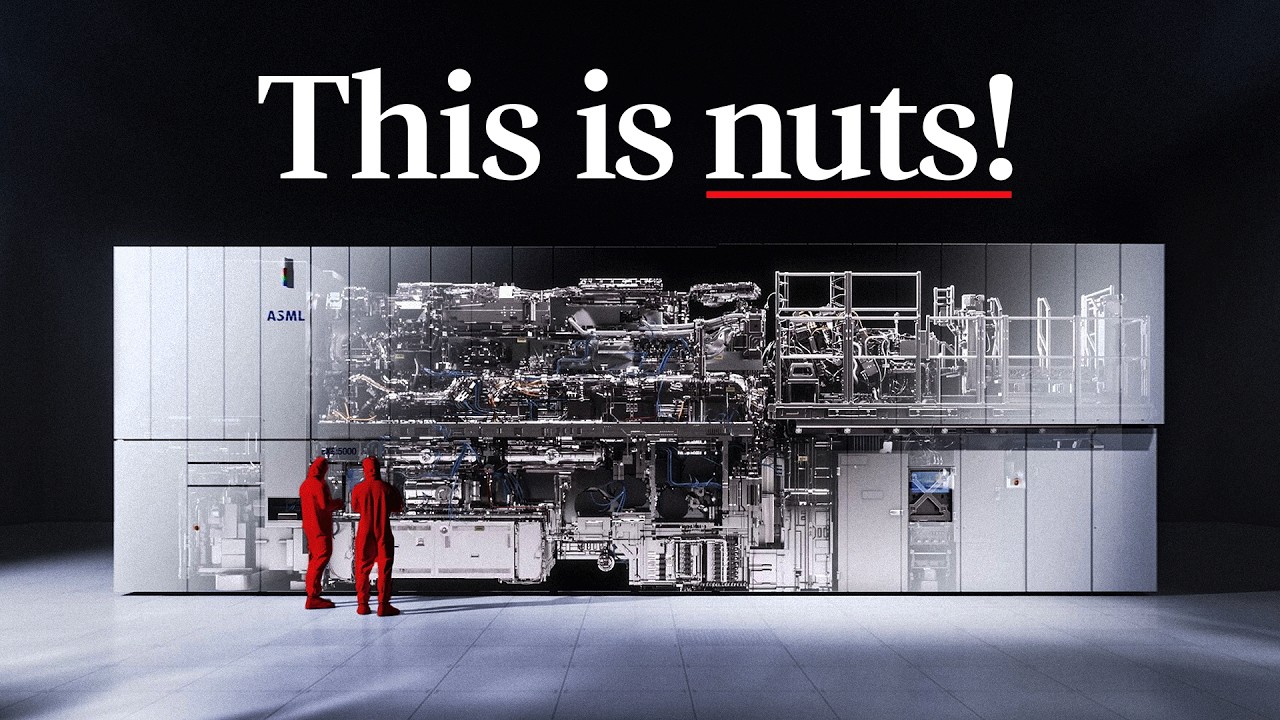

- Holy. This is a video

about the most complicated

[01:08] (68.56s)

commercial product humanity's ever built.

[01:11] (71.44s)

That's insane.

[01:12] (72.64s)

It costs a whopping $400 million,

[01:15] (75.12s)

and it is so bizarre that I

want to introduce it to you

[01:18] (78.08s)

with a thought experiment.

[01:20] (80.24s)

Imagine you are shrunk

down to the size of an ant,

[01:25] (85.12s)

and you are given a laser

that's strong enough to melt

[01:27] (87.92s)

through metal like butter.

[01:29] (89.76s)

Next, a tiny droplet of

molten tin, roughly the size

[01:32] (92.72s)

of a white blood cell, is

shot out in front of you

[01:35] (95.36s)

around 250 kilometers per hour.

[01:38] (98.00s)

And your task is to hit

this not once, not twice,

[01:41] (101.28s)

but three times in a

row in 20 microseconds

[01:44] (104.00s)

with your little laser.

[01:45] (105.84s)

Well, that is exactly

what this machine does.

[01:48] (108.40s)

It hits one tiny tin droplet

three times in a row,

[01:51] (111.68s)

heating each one up to over 220,000 Kelvin.

[01:55] (115.28s)

That's roughly 40 times hotter

than the surface of the sun.

[01:58] (118.96s)

And it doesn't just hit one droplet,

[02:01] (121.28s)

it hits 50,000 droplets

every single second.

[02:05] (125.28s)

How often do you miss a laser shot?

[02:06] (126.92s)

- We don't miss them.

[02:08] (128.48s)

- What you do 150,000

laser shots a second,

[02:12] (132.88s)

and you don't miss one exactly.

[02:15] (135.68s)

The same machine also contains mirrors

[02:17] (137.68s)

that might just be the smoothest

objects in the universe.

[02:21] (141.28s)

If you scale one up to

the size of the earth,

[02:23] (143.52s)

then the largest bump would be no thicker

[02:25] (145.68s)

than a playing card's.

[02:27] (147.04s)

On top of that, it is

able to overlay one layer

[02:29] (149.44s)

of a chip perfectly on top of another

[02:31] (151.36s)

and never be off by more than five atoms.

[02:34] (154.40s)

And this is all happening

while parts of the machine whip

[02:37] (157.20s)

around at accelerations of

over 20 g's.

[02:40] (160.80s)

For 30 years, almost everyone thought

[02:42] (162.88s)

that actually building this

machine was impossible,

[02:46] (166.16s)

and yet it exists.

[02:48] (168.16s)

There is only one company in

the world that can make it.

[02:51] (171.68s)

So what is this company

[02:53] (173.04s)

and what is this impossible

machine they've built?

[02:56] (176.08s)

This video is sponsored by Brilliant.

[02:58] (178.00s)

More about them at the end of the show.

[03:00] (180.32s)

Now, just as a quick aside, the makers

[03:02] (182.40s)

of this machine didn't

actually sponsor this video.

[03:05] (185.20s)

We just thought that the science

[03:06] (186.64s)

and engineering here

were so cool that we had

[03:09] (189.12s)

to make a video about it.

[03:10] (190.56s)

So let's jump straight in.

[03:12] (192.40s)

- To make a microchip, you start

[03:14] (194.40s)

by taking silicon

dioxide, usually from sand,

[03:16] (196.80s)

and purifying it into ultrapure,

[03:19] (199.20s)

nearly a hundred percent silicon chunks,

[03:22] (202.48s)

which is then melted down

in a special furnace.

[03:25] (205.60s)

Next, you lower a small

seed crystal into the vat.

[03:28] (208.72s)

Silicon atoms attach to the

crystal extending its structure.

[03:32] (212.56s)

Then you slowly raise the seed

crystal while rotating it.

[03:35] (215.76s)

And this results in a large

single crystal silicon ingot.

[03:39] (219.16s)

- This is where the seed

crystal would be. Yeah.

[03:41] (221.36s)

And then you pull it out. Can I touch it?

[03:42] (222.92s)

- Yeah, you can. It seems

like you would not be able

[03:46] (226.00s)

to ho hold this from here.

[03:47] (227.84s)

- Yes.

- It even feels fragile

[03:50] (230.24s)

Like if you kinda.

- Don't snap it.

[03:52] (232.16s)

Yeah, I-I'm scared to break it.

[03:54] (234.08s)

- Yes.

- He's using more force.

[03:56] (236.20s)

- The ingot is then cut into wafers

[03:58] (238.48s)

with diamond wire saws

up to 5,000 of them,

[04:02] (242.00s)

after which each wafer

is carefully polished.

[04:05] (245.04s)

Next, it's coated with a

light sensitive material

[04:07] (247.28s)

called photoresist.

[04:08] (248.72s)

There are different kinds,

[04:09] (249.76s)

but in a positive

photoresist, the areas exposed

[04:12] (252.64s)

to light become weaker and more soluble.

[04:15] (255.12s)

So if you shine light

through a patterned mask,

[04:17] (257.44s)

you can selectively weaken

parts of that coating.

[04:20] (260.16s)

Then you rinse the wafer

with a basic solution

[04:22] (262.40s)

to wash away the exposed photoresist,

[04:24] (264.88s)

leaving the design imprinted.

[04:27] (267.76s)

So now you can actually

turn this pattern into

[04:30] (270.16s)

physical structures.

[04:31] (271.28s)

This is often done by etching

into the uncovered silicon

[04:34] (274.24s)

by using either chemicals or plasma.

[04:36] (276.80s)

And then you deposit a metal like copper

[04:39] (279.04s)

to fill in those etched lines.

[04:41] (281.44s)

As a last step, you wash away

the remaining photoresist,

[04:44] (284.88s)

and now you've made a

single layer of the chip.

[04:48] (288.32s)

We've simplified this cycle

down to the main steps.

[04:50] (290.72s)

Coat, expose, etch, and deposit.

[04:53] (293.12s)

It repeats for every single chip layer,

[04:55] (295.36s)

and depending on the chip,

there could be anywhere from ten

[04:57] (297.92s)

to a hundred layers.

[04:59] (299.44s)

The bottom layer is the transistors.

[05:01] (301.60s)

This is the most complicated

layer requiring hundreds

[05:04] (304.08s)

of steps that all need to be perfect.

[05:06] (306.72s)

The higher layers are a little easier.

[05:09] (309.20s)

These are the metal wires

that carry signals and power.

[05:12] (312.40s)

By the end, the completed wafer

can have hundreds of chips,

[05:15] (315.36s)

which are then cut into

separate pieces, packaged

[05:17] (317.76s)

and put into products.

[05:20] (320.08s)

But by far the hardest

[05:21] (321.28s)

and most crucial step in the process is

[05:23] (323.60s)

where you shine light through

the mask and onto the wafer.

[05:26] (326.64s)

This is photolithography, and that's

[05:28] (328.72s)

because this step determines

[05:30] (330.56s)

how small you can make the features.

[05:32] (332.88s)

- At first, it seems simple light passes

[05:36] (336.00s)

through the openings and it

gets blocked by all the rest.

[05:39] (339.60s)

But as you try to print smaller

[05:41] (341.44s)

and smaller features, the

gaps in the mask start

[05:44] (344.08s)

to approach the wavelength of the light,

[05:46] (346.24s)

and that causes problems.

[05:48] (348.08s)

- And we can actually show it

[05:49] (349.52s)

because I happen to have a,

[05:51] (351.28s)

this is a mask. This is a reticle.

[05:52] (352.84s)

- A reticle or a mask carries

the design of one chip layer.

[05:56] (356.80s)

This redle is filled

with microscopic lines

[05:59] (359.04s)

and gaps around 670 nanometers across.

[06:01] (361.72s)

- And if I take like a laser pointer,

[06:03] (363.76s)

so this is a red laser.

[06:05] (365.04s)

- Yep. - If I shine it through

it, then you see this here,

[06:09] (369.00s)

- The laser has a wavelength

of around 650 nanometers.

[06:13] (373.60s)

When light hits the reticle,

it's wavefronts bend

[06:16] (376.40s)

as they pass through each gap.

[06:18] (378.16s)

So each gap sends out waves

that spread out and overlap.

[06:21] (381.84s)

Now let's just look at the

light from these two gaps.

[06:24] (384.88s)

When the peaks of one wave

line up with the troughs

[06:27] (387.68s)

of the other, we say that

the two waves are out of phase

[06:30] (390.72s)

and they cancel each other out.

[06:32] (392.32s)

So you get dark spots,

[06:33] (393.84s)

and when the peaks line up with the peaks,

[06:35] (395.68s)

the two waves are in phase, they add up

[06:38] (398.16s)

and you get bright spots.

[06:39] (399.76s)

You get interference.

[06:41] (401.19s)

- Yeah. - Right. And you get

a diffraction pattern.

[06:43] (403.00s)

- Now, diffraction is inevitable.

[06:45] (405.92s)

So instead of fighting it,

designers actually use it

[06:48] (408.64s)

to get the patterns they want.

[06:50] (410.64s)

They kind of work backwards

from the eventual pattern they

[06:53] (413.36s)

want on the wafer,

[06:54] (414.48s)

and they design the slits so

[06:56] (416.32s)

that diffraction will occur in such a way

[06:58] (418.32s)

that it creates the

pattern that they want.

[07:00] (420.64s)

- You see three dots, the middle

[07:02] (422.96s)

dot, that's the original one.

[07:04] (424.56s)

That's the zero order.

[07:05] (425.84s)

And then on the left

[07:06] (426.88s)

and the right, you can see

the first and the minus first.

[07:10] (430.16s)

Now, in order for us

[07:11] (431.84s)

to have this image resolved

on the wafer, you need

[07:15] (435.68s)

to capture the zero and the

first and the minus first order.

[07:19] (439.28s)

- The smaller you make the features,

[07:20] (440.96s)

the larger this angle

alpha between the zero

[07:23] (443.28s)

and first orders becomes.

[07:25] (445.12s)

So the larger your lens needs

to be to capture the light.

[07:28] (448.88s)

The size of the lens is described

by the numerical aperture

[07:32] (452.48s)

or na for short, which is

just the sine of this angle.

[07:36] (456.40s)

So the larger that is,

[07:37] (457.76s)

the smaller the features you can print.

[07:40] (460.24s)

But there is a hard limit to

[07:41] (461.84s)

how large your lens system

can be, when this angle is 90

[07:44] (464.92s)

degrees and your numerical aperture is one

[07:47] (467.28s)

well your lens would have to be infinite.

[07:49] (469.60s)

Fortunately, there is one

other thing we can change.

[07:52] (472.96s)

- This is a red laser. Yeah.

[07:55] (475.52s)

And a red laser has a wavelength

[07:57] (477.20s)

of 650 nanometers, I would say.

[08:00] (480.63s)

- Yeah.

- And if I take a green laser

[08:03] (483.44s)

and this one has a wavelength

of 532, then you can see

[08:07] (487.84s)

that the green dots are closer

spaced than the red dots.

[08:12] (492.96s)

- That's because the light

from the two different gaps

[08:15] (495.84s)

doesn't have to travel as far

to match up in phase again.

[08:19] (499.20s)

So the orders end up closer together.

[08:21] (501.52s)

So with a smaller wavelength,

[08:22] (502.80s)

you can print smaller

patterns using the same lens.

[08:26] (506.32s)

All of this is captured

by the Rayleigh equation,

[08:28] (508.80s)

which determines the

smallest feature, size

[08:30] (510.80s)

or critical dimension.

[08:32] (512.64s)

- But since there's a limit to

[08:35] (515.04s)

how much you can increase

the numerical aperture, I mean to one.

[08:38] (518.48s)

Over time, the only

way to keep making smaller

[08:40] (520.80s)

and smaller features is

[08:42] (522.48s)

by using shorter and shorter wavelengths.

[08:44] (524.72s)

So this is exactly what happened up

[08:46] (526.64s)

until the late 1990s when

the industry settled on 193

[08:50] (530.64s)

nanometer deep UV light, this

was the light that was used

[08:54] (534.40s)

to make all of the most

advanced chips right until

[08:57] (537.12s)

around 2015.

[08:58] (538.80s)

But by that point, scientists

had reached a limit to

[09:01] (541.68s)

how small they could make the features.

[09:03] (543.36s)

And Moore's law was about

to run into a brick wall.

[09:06] (546.80s)

So a radical change was needed, a change

[09:09] (549.68s)

that had been brewing for around 30 years.

[09:14] (554.24s)

All the way back in the 1980s.

[09:16] (556.08s)

Japanese scientist, Hiroo Kinoshita,

came up with a crazy idea.

[09:20] (560.72s)

Why not use much shorter

wavelengths like x-rays of

[09:23] (563.68s)

around 10 nanometers?

[09:25] (565.12s)

In theory, that should allow you

[09:26] (566.48s)

to print much smaller features,

[09:28] (568.64s)

but you quickly run into a problem.

[09:30] (570.72s)

X-rays at these wavelengths

have enough energy

[09:32] (572.96s)

to eject electrons from their atoms,

[09:35] (575.20s)

so most materials absorb them.

[09:37] (577.84s)

But unlike medical X-rays

which have wavelengths shorter

[09:41] (581.04s)

than one nanometer, these

are still long enough

[09:43] (583.44s)

to interact with air

[09:44] (584.88s)

So air absorbs them too.

[09:46] (586.96s)

That meant that Kinoshita's

setup had to be in a vacuum,

[09:50] (590.48s)

but even worse, he couldn't

use lenses to focus the light

[09:53] (593.68s)

because the lenses would absorb it too.

[09:57] (597.20s)

So it seemed like this idea would never work.

[10:01] (601.20s)

But around 1983, Kinoshita

stumbled on a paper

[10:04] (604.08s)

by Jim Underwood and Troy Barbee.

[10:06] (606.16s)

Their work focused on special mirrors

[10:08] (608.08s)

that could reflect

x-rays with a wavelength

[10:10] (610.08s)

of 4.48 nanometers.

[10:12] (612.40s)

So Kinoshita was intrigued.

[10:14] (614.56s)

Curved mirrors can focus

light just like lenses do.

[10:17] (617.28s)

If he could figure out how

to make these special mirrors

[10:19] (619.28s)

for the wavelength he was using,

[10:20] (620.96s)

then this could be another

way to do photolithography.

[10:24] (624.00s)

The mirrors work something like this.

[10:27] (627.68s)

When light crosses from one

medium to another, say from air

[10:30] (630.80s)

to glass, it bends or refracts.

[10:33] (633.20s)

Some of it goes through

and part reflects back.

[10:36] (636.00s)

How much gets reflected depends

on things like the angle,

[10:38] (638.72s)

the light's polarization.

[10:40] (640.32s)

And most importantly

for us, the difference

[10:42] (642.72s)

between the refractive

indices of the two media.

[10:45] (645.28s)

The larger that difference,

the more light is reflected.

[10:48] (648.48s)

And Underwood and Barbee

used that principle.

[10:51] (651.28s)

They made a super thin layer of tungsten,

[10:53] (653.52s)

less than one nanometer,

thick, thin enough

[10:55] (655.92s)

that x-rays could pass

[10:57] (657.20s)

through without

immediately being absorbed.

[10:59] (659.44s)

When x-rays hit the layer

at a specific angle,

[11:02] (662.16s)

the tungsten reflected less than 1%.

[11:04] (664.96s)

Then they carefully tuned

the layer thickness.

[11:07] (667.36s)

So the path length of the

transmitted x-rays was only one

[11:10] (670.64s)

quarter of its wavelength.

[11:12] (672.56s)

Then they added another layer.

[11:14] (674.24s)

This time out of carbon,

[11:15] (675.76s)

it has a higher refractive

index than tungsten

[11:17] (677.92s)

for wavelengths of 4.48 nanometers.

[11:20] (680.56s)

The x-rays hit the boundary

and a little bit more reflects,

[11:24] (684.48s)

but this time the phase is inverted

[11:26] (686.48s)

or it's changed by half a wavelength.

[11:28] (688.96s)

This happens when any light

moves from a lower refractive

[11:31] (691.76s)

index to a higher one.

[11:33] (693.76s)

Now, by the time this new

reflected wave reaches the

[11:36] (696.24s)

tungsten boundary, it has

traveled another quarter

[11:38] (698.56s)

of its wavelength for a

half wavelength in total.

[11:41] (701.60s)

So the two phases line up

[11:43] (703.20s)

and the waves interfere constructively.

[11:45] (705.44s)

Underwood and Barbee kept

doing this trick for a total

[11:47] (707.92s)

of 76 alternating layers, so

[11:50] (710.24s)

that in total they could reflect back much

[11:52] (712.56s)

more of the x-rays.

[11:55] (715.44s)

Now, they only managed to

reflect around 6% of the light,

[11:58] (718.48s)

but it was a proof of principle

[12:00] (720.08s)

that you could reflect x-rays.

[12:02] (722.24s)

- So Kinoshita saw the possibilities.

[12:05] (725.68s)

He got to work, and

[12:06] (726.96s)

after around two years, his team designed

[12:08] (728.88s)

and built three tungsten carbon

curved multi-layer mirrors

[12:12] (732.48s)

to reflect 11 nanometer light.

[12:14] (734.96s)

And with it, he managed to

print lines four microns

[12:17] (737.84s)

or 4,000 nanometers thick,

proving that at least in theory,

[12:22] (742.24s)

x-ray lithography was possible.

[12:25] (745.28s)

A year later in 1986, he

went to present his findings

[12:28] (748.64s)

to the Japanese Society

[12:30] (750.00s)

of Applied Physics.

[12:31] (751.36s)

Proud and excited, he explained his setup

and showed his image.

[12:34] (754.88s)

But to his horror, the

audience refused to believe it.

[12:38] (758.32s)

Unfortunately, the audience

[12:41] (761.12s)

was highly skeptical of my talk.

[12:44] (764.72s)

Kinoshita was devastated.

[12:46] (766.64s)

He later said, people

seemed unwilling to believe

[12:49] (769.52s)

that we had actually made

an image by bending x-rays,

[12:52] (772.72s)

and they tended to regard the whole thing

[12:54] (774.56s)

as a big fish story.

[12:56] (776.40s)

- Nobody believed that this

was a viable way forward,

[13:00] (780.48s)

and unfortunately,

[13:01] (781.76s)

the reaction was at

least somewhat justified.

[13:05] (785.12s)

First, this light isn't naturally produced

[13:07] (787.20s)

by anything on earth.

[13:08] (788.64s)

The closest natural source is the sun.

[13:12] (792.40s)

We had to basically build an

artificial sun here on Earth.

[13:17] (797.44s)

Most scientists, including Kinoshita,

[13:19] (799.36s)

produced x-ray light using a particle

[13:21] (801.20s)

accelerator or a synchrotron.

[13:22] (802.64s)

- It gives an enormous amount of power.

[13:25] (805.20s)

It's as big as a soccer field.

You can fuel the whole fab.

[13:28] (808.48s)

The problem is if the light goes out, the

[13:30] (810.16s)

whole fab goes out.

[13:31] (811.28s)

- So each machine needed

its own power source.

[13:35] (815.20s)

But even if you could

produce the light, you'd need

[13:37] (817.44s)

to make incredibly smooth

mirrors to actually focus

[13:40] (820.80s)

and print those tiny features.

[13:42] (822.72s)

You would need the smoothest

objects in the universe.

[13:46] (826.12s)

- Okay, so I got a football

and I've got a bouncy ball

[13:49] (829.28s)

and a cobblestone street.

[13:50] (830.72s)

Now what do you think is

gonna happen when I drop them?

[13:54] (834.48s)

The football basically

bounces straight up,

[13:56] (836.48s)

but for the bouncy ball, it

just shoots off to the side.

[13:59] (839.68s)

And it's because the

surface is relatively flat

[14:02] (842.16s)

for the football, which is much larger,

[14:03] (843.92s)

but it's super rough for the bouncy ball.

[14:06] (846.56s)

And a similar thing happens with mirrors.

[14:08] (848.80s)

If the surface is super

rough compared to the size

[14:11] (851.36s)

of the wavelength, then the

light scatters randomly.

[14:14] (854.64s)

Now it might look smooth,

[14:15] (855.92s)

but if you zoom into a

mirror, you find something

[14:18] (858.00s)

that looks like this, you

find all these crazy bumps.

[14:22] (862.16s)

And now to measure the roughness,

[14:23] (863.52s)

what you do is you take

the average of these bumps

[14:26] (866.32s)

and that will give you your mean line.

[14:28] (868.24s)

Now, for a normal household mirror,

[14:30] (870.24s)

the average height is

about 4,000 silicon atoms.

[14:34] (874.24s)

But for Kinoshita's

mirrors, which not only needed

[14:37] (877.04s)

to reflect x-ray light,

[14:38] (878.16s)

which has a hundred

times shorter wavelength,

[14:40] (880.32s)

but also needed to minimize

scattering, you know, so

[14:42] (882.72s)

that all the photons make

it onto the wafer, it needed

[14:45] (885.44s)

to be way more smooth.

[14:47] (887.12s)

It needed to be atomically smooth.

[14:49] (889.20s)

In fact, the average bump could only about

[14:51] (891.52s)

2.3 silicon atoms thick.

[14:53] (893.96s)

- If one mirror would

be the size of Germany,

[14:56] (896.72s)

the biggest bump would be

about a millimeter high.

[14:58] (898.96s)

- But Kinoshita refused to give up.

[15:01] (901.36s)

- However, my belief did not change.

[15:03] (903.68s)

- And soon help would come

from an unlikely place.

[15:07] (907.52s)

- Across the Pacific

around 70 kilometers east

[15:10] (910.48s)

of San Francisco is Lawrence

Livermore National Lab, a lab

[15:13] (913.84s)

that was born outta the

Cold War, heavily funded

[15:16] (916.40s)

by the US government, and built

[15:17] (917.92s)

for one purpose and one purpose only.

[15:20] (920.40s)

Nuclear weapons.

[15:22] (922.08s)

The lab was founded by the

inventor of the cyclotron,

[15:24] (924.88s)

Ernest Lawrence, and the father

[15:26] (926.48s)

of the hydrogen bomb Edward Teller.

[15:28] (928.72s)

And over its lifetime,

[15:29] (929.84s)

they designed over 10 fusion

type nuclear warheads.

[15:33] (933.28s)

So part of their research

focused on what happens

[15:35] (935.68s)

inside nuclear fusion reactions.

[15:38] (938.48s)

Fusion reactions released

a lot of x-ray light, light

[15:41] (941.44s)

that they had never been

able to capture and analyze.

[15:44] (944.64s)

But now, using those

special multilayer mirrors,

[15:47] (947.68s)

there was a chance

[15:48] (948.80s)

- One of the scientists tasked

[15:50] (950.88s)

with making this work was Andrew Hawryluk.

[15:53] (953.36s)

And within a few years, he

[15:54] (954.96s)

and his team used multilayer mirrors

[15:56] (956.80s)

to reflect some X-ray light.

[15:59] (959.28s)

But then in 1987,

[16:00] (960.96s)

Andy got a visit from a

professor from Cornell.

[16:03] (963.76s)

- He was very impressed with the

[16:05] (965.36s)

technologies that we developed.

[16:06] (966.56s)

And he looked at me at the end of the day

[16:08] (968.08s)

and said, this is all very interesting

[16:09] (969.84s)

and very neat and stuff.

[16:11] (971.04s)

But his words,

[16:12] (972.88s)

that I'll remember it

to the day I die, was,

[16:14] (974.80s)

can you do anything

useful with this stuff?

[16:17] (977.16s)

And this was the day before

a Christmas shutdown in 1987.

[16:22] (982.24s)

And I was so inflamed by that,

that comment that I went home

[16:26] (986.96s)

and for the next 10 days,

[16:28] (988.16s)

I wrote up a multi-page white paper.

[16:30] (990.56s)

- He applied these mirrors to lithography,

[16:33] (993.04s)

to print chips using x-rays

around five months later.

[16:36] (996.64s)

And he presented his

findings at a conference.

[16:39] (999.60s)

But like Kinoshita, it was not

the response he was hoping for.

[16:43] (1003.44s)

- It was extremely negative.

[16:47] (1007.04s)

That was the low point in my career.

[16:49] (1009.84s)

I was literally laughed off the stage.

[16:52] (1012.24s)

And I kid you not every

person who I looked up

[16:56] (1016.08s)

to in the field, they

were listening to my talk

[16:58] (1018.56s)

and they came up to the microphone

[17:00] (1020.64s)

and told me basically

why it wouldn't work,

[17:04] (1024.24s)

how stupid an idea it was.

[17:06] (1026.88s)

Later that week, I flew back

[17:08] (1028.24s)

and the following Monday, my

boss asked me, how did it go?

[17:12] (1032.64s)

And I looked at him

[17:13] (1033.60s)

and I said, I will

never speak of it again.

[17:18] (1038.56s)

- But then three days later,

[17:20] (1040.40s)

he gets a phone call from

someone named Bill Brinkman

[17:23] (1043.68s)

from Bell Labs.

[17:24] (1044.95s)

- And so I walked over to my boss

[17:26] (1046.08s)

and I said, just got this phone call

[17:28] (1048.16s)

from a guy named Bill Brinkman,

[17:29] (1049.36s)

do you know who he is?

And my boss's eyes popped open

[17:32] (1052.24s)

and said, of, yeah, and

he's the executive vice

[17:34] (1054.40s)

president of AT&T.

[17:35] (1055.84s)

And I said, well, he just called me

[17:37] (1057.52s)

and asked me to fly out to

New Jersey and give a talk.

[17:41] (1061.12s)

The response from my boss said it all.

[17:44] (1064.96s)

He basically said,

well, you, you gotta go.

[17:47] (1067.68s)

- At Bell Labs found fellow believers

[17:50] (1070.72s)

and it couldn't have

come at a better time.

[17:53] (1073.12s)

Over the past 30 years,

[17:54] (1074.40s)

the US government had invested billions

[17:56] (1076.48s)

of dollars into national labs

[17:58] (1078.08s)

to maintain the country's

technological edge

[18:00] (1080.40s)

during the Cold War.

[18:02] (1082.32s)

But by the late 1980s, the

Cold War was slowing down

[18:05] (1085.92s)

and all these labs were

sitting on research

[18:08] (1088.00s)

that had commercial potential.

[18:09] (1089.92s)

So the government encouraged

the labs to partner

[18:12] (1092.32s)

with US companies to turn

that research into products

[18:15] (1095.76s)

and to stimulate the economy.

[18:17] (1097.60s)

And the government would

then supply seed money.

[18:20] (1100.24s)

And so Bell Labs partnered

with Andy's labs

[18:22] (1102.72s)

and two others to keep

developing x-ray lithography.

[18:27] (1107.12s)

And by 1993, the first

international conference

[18:30] (1110.08s)

for x-ray lithography was

held in Japan near Mount Fuji.

[18:34] (1114.72s)

In the opening address,

Kinoshita said that as long

[18:38] (1118.00s)

as we do not lose the desire

that has sprung from within us,

[18:41] (1121.12s)

technology will steadily advance from the

[18:43] (1123.36s)

micro to the nano to the pico.

[18:46] (1126.48s)

They even gave the technology a new name,

[18:48] (1128.80s)

extreme ultraviolet lithography or just

[18:51] (1131.84s)

- EUV.

[18:53] (1133.84s)

But then in 1996,

[18:55] (1135.36s)

the US government cut

funding for the project.

[18:58] (1138.40s)

This spelled disaster for the

big chip companies like Intel,

[19:02] (1142.08s)

the industry estimated

[19:03] (1143.20s)

that the 193 nanometer

lithography tools would fall

[19:06] (1146.24s)

behind Moore's Law by 2005,

[19:09] (1149.36s)

but there were no other alternatives.

[19:13] (1153.44s)

So Intel, Motorola, AMD and

other companies got together

[19:16] (1156.80s)

and invested $250

million to keep it going,

[19:20] (1160.00s)

making it the largest investment ever

[19:21] (1161.92s)

by private industry in a Department

[19:23] (1163.84s)

of Energy research project.

[19:26] (1166.00s)

By the year 2000, the

labs had produced this,

[19:28] (1168.56s)

the engineering test stand.

[19:30] (1170.40s)

It was the first fully

functioning EUV prototype.

[19:33] (1173.68s)

It produced 9.8 watts of

13.4 nanometer EUV light,

[19:38] (1178.08s)

which was then reflected by

eight mirrors from the source

[19:40] (1180.80s)

to the mask to the wafer.

[19:42] (1182.48s)

It could print 70 nanometer features

[19:44] (1184.64s)

and it proved that EUV could work.

[19:47] (1187.36s)

- It was a milestone to get the

[19:49] (1189.20s)

engineering test stand to work.

[19:50] (1190.64s)

It demonstrated to people

like Intel that, you know,

[19:54] (1194.24s)

good engineering will get us there.

[19:55] (1195.76s)

- And then it seems like

you've got the prototype

[19:58] (1198.96s)

shouldn't be too hard to

then commercialize it.

[20:02] (1202.32s)

- That's what they thought.

- But the prototype had

[20:06] (1206.48s)

a major flaw.

[20:07] (1207.60s)

It could only print about

10 wafers per hour.

[20:10] (1210.24s)

And to make EUV economically

viable, it would have

[20:12] (1212.96s)

to print hundreds of wafers per hour

[20:15] (1215.20s)

24/7, 365 days a year.

[20:18] (1218.56s)

The main reason output was so slow was

[20:20] (1220.88s)

because the light reflected

off of eight mirrors

[20:23] (1223.12s)

and the reticle, which

is also a mirror just

[20:25] (1225.60s)

with the design imprinted.

Traditional masks that allow light

[20:29] (1229.20s)

to pass through don't work

[20:30] (1230.48s)

because well, they absorb all the light.

[20:33] (1233.44s)

Each mirror had a reflectivity

of around 70%, which is close

[20:36] (1236.88s)

to the max, but

[20:38] (1238.16s)

after nine bounces, you are

only left with 4% of the light,

[20:42] (1242.40s)

which means that out of every 100 photons,

[20:45] (1245.20s)

only four make it to the wafer.

[20:48] (1248.16s)

So you might think just

use way fewer mirrors,

[20:51] (1251.52s)

but that only works up to a point.

[20:53] (1253.60s)

When you focus light

with any optical system,

[20:56] (1256.08s)

you always get some distortion.

[20:58] (1258.16s)

For example, ray's that pass

[20:59] (1259.52s)

through the outer edges of most lenses.

[21:01] (1261.28s)

Focus light slightly different

from those near the center.

[21:04] (1264.08s)

This is called spherical aberration.

[21:06] (1266.08s)

And normal cameras correct for this

[21:07] (1267.84s)

and other aberrations by

using multiple lenses.

[21:10] (1270.72s)

And a mirror system is no different.

[21:12] (1272.72s)

- You need to have a

certain amount of mirrors

[21:16] (1276.08s)

before you can say, I have

my aberrations under control.

[21:20] (1280.48s)

In reality, the systems of today have,

[21:22] (1282.84s)

have, have six mirrors

[21:24] (1284.12s)

- That helps a little.

[21:25] (1285.76s)

But after reflecting off six mirrors

[21:28] (1288.16s)

and the reticle, you

are still only left with

[21:30] (1290.32s)

around 8% of your light.

[21:32] (1292.16s)

So they needed to drastically

increase the source power

[21:34] (1294.80s)

to at least a hundred watts.

[21:36] (1296.80s)

Now to most companies,

[21:38] (1298.40s)

that tenfold increase seemed impossible.

[21:41] (1301.04s)

Even people who worked on

the engineering test noted

[21:43] (1303.68s)

that while EUV technology

itself is a done deal,

[21:47] (1307.28s)

there were six zillion

engineering challenges

[21:50] (1310.16s)

to make it a fab line reality.

[21:52] (1312.72s)

And so one by one American

companies walked away from

[21:56] (1316.32s)

developing a full UV lithography machine

[21:59] (1319.12s)

that left just one

company, ASML.

[22:03] (1323.12s)

ASML, which used to stand for advanced

semiconductor materials lithography,

[22:07] (1327.12s)

is located in a small nondescript town

in the Netherlands.

[22:10] (1330.32s)

It spun off from Philips

back in the eighties

[22:12] (1332.48s)

with little more than a shed

[22:13] (1333.76s)

and a barely working

wafer stepper to its name.

[22:16] (1336.72s)

But Phillips also gave them

people, Jos Benschop,

[22:19] (1339.68s)

ASML's first researcher

[22:21] (1341.20s)

and Martin van den Brink, who would

eventually become ASML's CTO,

[22:25] (1345.12s)

and EUV's greatest champion.

[22:27] (1347.16s)

- And he is really like the

Steve Jobs of lithography.

[22:30] (1350.16s)

And he saw EUV coming

[22:31] (1351.92s)

- A ML had joined the US

EUV consortium earlier

[22:35] (1355.04s)

and now it became their task to find a way

[22:37] (1357.92s)

to commercialize EUV.

[22:39] (1359.44s)

They would work together with

their German partner Zeiss,

[22:42] (1362.08s)

where Zeiss would take

care of the mirrors,

[22:43] (1363.76s)

and ASML would focus on the light source.

[22:47] (1367.20s)

One of the first decisions

when making any lithography

[22:49] (1369.92s)

system is deciding

which wavelength to use.

[22:52] (1372.56s)

- In the early days, anything between five

[22:54] (1374.72s)

and 14 nanometers was, was explored.

[22:58] (1378.08s)

The thing is

you need to find a source

[23:00] (1380.56s)

and you need to find

optics that reflect the wavelengths.

[23:03] (1383.00s)

- Right. - So you have to

look for the combination.

[23:05] (1385.12s)

- Underwood and Barbee

had already made mirrors

[23:07] (1387.36s)

that could reflect light

of around four nanometers.

[23:10] (1390.00s)

And since that wavelength is so small,

[23:11] (1391.92s)

it seems like the obvious choice,

[23:14] (1394.24s)

but the maximum reflectivity

[23:15] (1395.76s)

for those mirrors was only around 20%.

[23:18] (1398.24s)

So after hitting six mirrors

[23:20] (1400.32s)

and the reticle, you are just left

[23:22] (1402.08s)

with 0.00128% of the light,

[23:26] (1406.72s)

which is way too low.

[23:28] (1408.80s)

Fortunately, further researchers

also looked at two other

[23:31] (1411.76s)

pairs, silicon

[23:33] (1413.12s)

and molybdenum, which had a

theoretical maximum reflectivity

[23:36] (1416.48s)

of 70% for wavelengths around

13 nanometers and molybdenum

[23:41] (1421.44s)

and beryllium with a theoretical

maximum reflectivity of 80%

[23:46] (1426.00s)

for wavelengths around 11 nanometers.

[23:48] (1428.32s)

So the choice seemed obvious, right?

[23:50] (1430.56s)

I mean, pick the shorter wavelength

[23:52] (1432.16s)

and the higher reflectivity,

[23:53] (1433.84s)

but it turns out that

beryllium is extremely toxic

[23:57] (1437.28s)

and it's also difficult to handle.

[23:59] (1439.44s)

So scientists focused on silicon

[24:01] (1441.68s)

and molybdenum instead

[24:03] (1443.68s)

To make the mirrors,

Zeiss used a process called sputtering.

[24:07] (1447.12s)

A target of coating material

is bombarded with either plasma

[24:10] (1450.64s)

or ions causing atoms

to be ejected, fly off

[24:14] (1454.16s)

and stick to the mirror.

[24:16] (1456.00s)

This is a messy process,

[24:17] (1457.52s)

so the layers end up

having bumps and gaps.

[24:20] (1460.16s)

- There was a nice trick

[24:21] (1461.68s)

that actually the team in

the Netherlands perfected

[24:25] (1465.28s)

with ion beam.

[24:26] (1466.56s)

You just shake it a little bit

[24:28] (1468.24s)

until the atoms falls in the

hole where it needs to be

[24:30] (1470.56s)

and then it's all flat

[24:31] (1471.96s)

- With the mirror design locked

in ASML needed a source for

[24:36] (1476.00s)

that specific wavelength.

[24:37] (1477.12s)

- So it was 13 point x. Yeah. Okay.

[24:40] (1480.00s)

Now the next good

question is what's the X?

[24:42] (1482.56s)

Now you look for the, now

you look for the source.

[24:45] (1485.44s)

So there are basically

three ways to generate EUV

[24:48] (1488.64s)

to build a sun on Earth.

[24:51] (1491.60s)

The first method,

[24:52] (1492.48s)

which early researchers

used was the synchrotron,

[24:55] (1495.12s)

but it was quickly rolled out

[24:56] (1496.64s)

because each machine

needed its own source.

[24:59] (1499.68s)

The other two methods are

based on the same principle.

[25:02] (1502.32s)

When an electron recombines

with an ion, the ion drops

[25:05] (1505.76s)

to a lower energy level

[25:07] (1507.20s)

and it releases that

excess energy as a photon.

[25:10] (1510.16s)

And if you choose the ion just right, then

[25:12] (1512.88s)

that photon will have exactly

the wavelength you need.

[25:16] (1516.32s)

Now, there are two ways

you can create those ions.

[25:19] (1519.12s)

The first is you take a metal, heat it up

[25:21] (1521.12s)

until you get a metal vapor,

[25:22] (1522.40s)

and then you apply a strong

electric field across it.

[25:25] (1525.92s)

This causes free electrons

to knock into nearby atoms

[25:28] (1528.80s)

and ionize them.

[25:30] (1530.88s)

If you then turn off the electric field,

[25:32] (1532.88s)

the electrons recombine with

the ions and produce light.

[25:36] (1536.64s)

This is discharge produced plasma.

[25:38] (1538.80s)

- That's the concept we use first.

[25:41] (1541.28s)

Because of its

relative simplicity.

[25:43] (1543.60s)

And we quickly got into a few watts.

[25:46] (1546.16s)

We wanted to get a hundred

watts and we struggled forever.

[25:49] (1549.56s)

- So you couldn't scale it.

- We could not scale it.

[25:52] (1552.24s)

They needed a drastic change.

[25:54] (1554.40s)

So they switched to the second method.

[25:56] (1556.56s)

This method uses a high powered laser

[25:58] (1558.48s)

to hit a target material creating a plasma

[26:01] (1561.12s)

that's more than 220,000

degrees Celsius hot.

[26:04] (1564.88s)

The electrons have so much energy

[26:06] (1566.64s)

that the nucleus can't

hold onto them anymore,

[26:09] (1569.20s)

and up to 14 electrons escape their orbits

[26:12] (1572.64s)

after the laser shuts off the electrons

[26:14] (1574.64s)

and ions recombine to produce light.

[26:17] (1577.68s)

This is laser produced plasma

[26:19] (1579.44s)

and it was the only method

that seemed scalable.

[26:23] (1583.68s)

In fact, this was the same method

[26:25] (1585.20s)

that the engineering test stand used.

A 1700 watt laser fired into

[26:29] (1589.36s)

a stream of seen on gas to

produce 13.4 nanometer lights.

[26:34] (1594.32s)

But Xenon had a big problem.

[26:36] (1596.56s)

The conversion efficiency that

is the ratio of usable lights

[26:40] (1600.00s)

to the amount of power

you put in was terrible.

[26:42] (1602.64s)

It was only around 0.5%.

[26:45] (1605.04s)

That's because Xenon

does emit light in the 13

[26:47] (1607.84s)

to 14 nanometer range.

[26:49] (1609.60s)

There's much more light

released around 11 nanometers.

[26:52] (1612.72s)

So most of the energy

went into making light

[26:54] (1614.88s)

that the mirrors couldn't reflect.

[26:57] (1617.04s)

Plus the laser didn't

ionize all the atoms.

[26:59] (1619.60s)

So leftover neutral, Xenon atoms

would strongly reabsorb some

[27:03] (1623.44s)

of that 13.4 nanometer light.

[27:06] (1626.56s)

So ASML started looking

at another material, tin.

[27:10] (1630.48s)

Now tin has a much higher emission peak

[27:12] (1632.64s)

around 13.5 nanometers,

which results in a five

[27:15] (1635.92s)

to 10 times higher conversion

efficiency than Xenon.

[27:19] (1639.12s)

But just like Xenon neutral tin

atoms also absorb EUV light.

[27:22] (1642.96s)

So they came up with a crazy idea

[27:25] (1645.44s)

to shoot one tiny tin droplet at a time.

[27:29] (1649.04s)

But to get the required

power, you would have to make

[27:31] (1651.20s)

and hit thousands of

droplets every second, all

[27:34] (1654.72s)

of which have to be the

exact same shape and size.

[27:39] (1659.04s)

But it turns out that you

can't instantly make thousands

[27:41] (1661.84s)

of tin droplets that are the exact same.

[27:44] (1664.48s)

So they found a workaround.

[27:46] (1666.72s)

To make the droplets, extremely pure

[27:48] (1668.96s)

tin is melted and pushed

through a microscopic nole

[27:51] (1671.92s)

by high pressure nitrogen.

[27:53] (1673.52s)

This nozzle vibrates at a high frequency,

[27:55] (1675.84s)

breaking the stream into tiny droplets.

[27:58] (1678.32s)

These droplets are irregular

in size, shape, velocity,

[28:01] (1681.60s)

and distance, and the

whole process is chaotic.

[28:04] (1684.24s)

- That's like our magic sauce is

[28:07] (1687.44s)

how do you modulate that tin jet?

[28:10] (1690.00s)

So that forms the droplets we

want and that they're stable.

[28:12] (1692.04s)

- I think we found some paper

that describe this process

[28:16] (1696.56s)

and it was sort of eyeopening to me

[28:19] (1699.04s)

that it seems like all the

droplets actually come out

[28:21] (1701.92s)

irregular out of the nozzle, but then

[28:24] (1704.32s)

before they reach the side

where they get hit by the laser,

[28:27] (1707.44s)

like the little irregular

droplets come together

[28:29] (1709.92s)

to form these perfectly spaced,

perfectly regular droplets

[28:33] (1713.60s)

that are about the same size and shape

[28:36] (1716.16s)

and all traveling at the same velocity.

[28:38] (1718.72s)

That feels like magic to me, Jason.

[28:40] (1720.40s)

- Yeah, it's, it's exactly that.

[28:42] (1722.24s)

It's how do you take a long

stream of a tin jet that wants

[28:46] (1726.72s)

to break up into all

these irregular droplets

[28:49] (1729.20s)

and like force onto it

[28:51] (1731.60s)

that is gonna collapse

into a single droplet

[28:53] (1733.76s)

and then happen again and again and again.

[28:55] (1735.84s)

- You also don't have that

many variables to play with.

[28:58] (1738.64s)

You've got the pressure with

which you push out the tin

[29:01] (1741.28s)

and at the frequency of the nozzle.

[29:03] (1743.44s)

Yeah, it seems like a

hard problem to solve.

[29:05] (1745.44s)

- There's not a whole lot

of variables to play with.

[29:07] (1747.92s)

And so mastering that

modulation of the jet is,

[29:12] (1752.40s)

is how we make the droplets.

[29:14] (1754.16s)

- But these droplets not

only have to be identical,

[29:17] (1757.92s)

they have to be moving incredibly fast.

[29:20] (1760.80s)

- What will happen is if the next droplet

[29:24] (1764.00s)

that's coming down the line is too close,

[29:26] (1766.32s)

then it'll actually get like disturbed

[29:28] (1768.80s)

and mess up the next plasma event.

[29:31] (1771.68s)

So we have a requirement which is both

[29:34] (1774.16s)

that we make 50,000 droplets per second,

[29:36] (1776.16s)

but also that they're

traveling extremely fast.

[29:39] (1779.24s)

- By 2011,

[29:40] (1780.88s)

their laser produced plasma

source reached 11 watts,

[29:44] (1784.32s)

which was more than

double what they managed

[29:46] (1786.24s)

with their previous source.

[29:47] (1787.92s)

But they were still limited

to just five wafers per hour.

[29:51] (1791.12s)

So they needed to increase

the power and fast

[29:54] (1794.16s)

because they promised they'd

hit 60 wafers per hour

[29:56] (1796.80s)

by the end of 2011.

[29:59] (1799.28s)

Unfortunately, this new method had a major flaw.

[30:02] (1802.72s)

Now the problem with the tin

issue, you hit the droplet,

[30:05] (1805.12s)

you generate EUV,

[30:06] (1806.48s)

with a very decent conversion efficiency.

[30:08] (1808.88s)

Where does the tin go?

[30:10] (1810.16s)

Because like, you know,

30 centimeters away.

[30:13] (1813.04s)

You have this atomically

flat, very beautiful,

[30:16] (1816.80s)

very expensive, mirror from our friends at ZEISS

[30:20] (1820.00s)

And in the early

days we would coat the thing

[30:22] (1822.72s)

within like this.

[30:24] (1824.28s)

- These machines need to run for a year.

[30:26] (1826.72s)

You're putting liters of tin

through this plasma event

[30:31] (1831.76s)

and a single nanometer of tin.

[30:33] (1833.60s)

If it was to land on that

collector mirror, you'd have

[30:36] (1836.00s)

to take a collector outta commission.

[30:37] (1837.68s)

We need to keep it almost

perfectly clean for, for a year.

[30:41] (1841.68s)

- Yeah. How do you even approach that?

[30:43] (1843.44s)

- So our, our, our main tool here is the

[30:45] (1845.68s)

hydrogen gas actually.

[30:46] (1846.96s)

- They fill the chamber

with low pressure hydrogen.

[30:50] (1850.32s)

This slows and cools

the tin particles down.

[30:53] (1853.12s)

And even if some tin

makes it to the collector,

[30:55] (1855.36s)

the hydrogen pulls it off

to form a gas called stannane.

[30:59] (1859.04s)

This way the machine cleans

the collectors while it's running.

[31:02] (1862.56s)

But that hydrogen gas also gets hot from all

[31:04] (1864.96s)

those tin explosions.

[31:06] (1866.40s)

So they need to keep flushing

new, cooler hydrogen into the

[31:09] (1869.68s)

system while flushing out

the stannane and hotter gas.

[31:13] (1873.36s)

But they have to get the pressure

[31:14] (1874.56s)

and the flow rate just right.

[31:16] (1876.32s)

I mean too little hydrogen

[31:17] (1877.92s)

and the mirrors would get too dirty,

[31:19] (1879.76s)

but too much hydrogen would

not only absorb too much EUV

[31:22] (1882.80s)

light, but it would also

cause the system to overheat.

[31:25] (1885.60s)

- But the question is

how much heat is there?

[31:28] (1888.64s)

How much energy is being

deposited into the gas?

[31:31] (1891.60s)

And we were stumped for quite some time.

[31:33] (1893.60s)

If you look at a EUV light

source, what you'll see is

[31:36] (1896.24s)

that it's, it's kinda like a globe

[31:39] (1899.04s)

of like purple-ish red light

[31:41] (1901.36s)

and you kinda ask yourself

like, why is that happening?

[31:43] (1903.92s)

So we bought an ultra fast camera.

[31:46] (1906.56s)

What we realized is that

after every plasma event,

[31:49] (1909.20s)

there's a shockwave

[31:51] (1911.36s)

that goes propagating

out into the hydrogen gas

[31:54] (1914.56s)

and it's extremely repeatable.

[31:57] (1917.20s)

And you think to yourself, there must be

[31:58] (1918.64s)

like an explanation for this.

[32:00] (1920.48s)

And there's this formula,

the Taylor–von Neumann–Sedov formula

[32:04] (1924.88s)

that explains point source

explosions in an environment

[32:07] (1927.84s)

and like say a nuclear

blast out to like supernova.

[32:11] (1931.44s)

So I took this formula, it like

exactly describes the data.

[32:14] (1934.96s)

It's just fantastic that

[32:16] (1936.96s)

we're seeing these like

little tiny little supernovas

[32:19] (1939.68s)

happening in our vessel

50,000 times a second.

[32:22] (1942.04s)

- And is that a fair

way to think about this,

[32:24] (1944.40s)

like creating mini supernova?

[32:26] (1946.48s)

- Yeah, it's actually pretty similar.

[32:28] (1948.64s)

It's almost like very similar to a,

[32:30] (1950.24s)

like a type one A supernova.

[32:31] (1951.60s)

It turns out where you

kind of have an object

[32:33] (1953.44s)

that just fully evaporates

and explodes apart.

[32:36] (1956.16s)

And when all that energy

goes into the hydrogen gas,

[32:39] (1959.36s)

it produces a a shock wave, a blast wave

[32:41] (1961.52s)

that comes flying out, which

is basically the same thing.

[32:44] (1964.24s)

If you look up in the night sky,

[32:45] (1965.52s)

there are these like remnants supernovas

[32:47] (1967.28s)

that you can see coming from space.

[32:48] (1968.92s)

- Using those energy calculations,

[32:51] (1971.04s)

they discovered they needed

[32:52] (1972.16s)

to flush the hydrogen at

incredibly high speeds

[32:54] (1974.88s)

around 360 kilometers per hour.

[32:57] (1977.52s)

That's more than a

category five hurricane,

[32:59] (1979.60s)

even if you know those

speeds are at low density.

[33:02] (1982.72s)

But 2012 came and went

[33:04] (1984.48s)

and they still didn't have enough power.

[33:06] (1986.88s)

In fact, by 2013, ASML

just reached 50 watts

[33:10] (1990.32s)

by shooting 50,000 tin droplets per second.

[33:13] (1993.28s)

But this increased power came at a price

[33:15] (1995.60s)

because more power means more heat.

[33:18] (1998.32s)

Heat that ends up slightly

shifting the mirrors resulting in

[33:21] (2001.92s)

misaligned light and

misaligned chip layers.

[33:25] (2005.12s)

So ZEISS built a nervous system

directly into the optics

[33:29] (2009.12s)

robot guided sensors

[33:30] (2010.40s)

that constantly measure the exact position

[33:32] (2012.64s)

and angle of each mirror down

[33:34] (2014.64s)

to the nanometer at the pico radian,

[33:37] (2017.12s)

which is absolutely insane.

[33:39] (2019.00s)

- So how accurate do we

need to control this mirror?

[33:42] (2022.64s)

Now one of the things you

can do a thought experiment.

[33:45] (2025.76s)

And I can place a

little laser on the side

[33:50] (2030.16s)

of this mirror, then we

go all the way to the moon

[33:53] (2033.68s)

and we put a dime here.

[33:56] (2036.40s)

So then this light

travels all the way here

[33:59] (2039.44s)

and then with the accuracy,

I can control this mirror.

[34:02] (2042.60s)

- Yes - I can decide

whether I point to this side

[34:06] (2046.72s)

of the dime or whether I point

to this side of the dime.

[34:10] (2050.16s)

- What? That's crazy.

[34:12] (2052.40s)

- So you can see that

the pointing accuracy is

[34:16] (2056.40s)

that's also in in pico radians.

[34:19] (2059.20s)

That is something very extreme.

[34:21] (2061.36s)

- This allowed them to control

the light even when the

[34:24] (2064.48s)

power increased.

[34:26] (2066.00s)

While Zeiss was doing a

stellar job with the optics,

[34:28] (2068.48s)

ASML was still struggling

with the power source.

[34:31] (2071.68s)

The problem was that the

tin droplets were too dense,

[34:34] (2074.80s)

meaning that most of the emitted

EUV light was still getting

[34:38] (2078.24s)

reabsorbed by the neutral atoms

[34:40] (2080.16s)

before it could ever reach

the collector mirror.

[34:42] (2082.28s)

- The way we blasted the droplet was

[34:44] (2084.80s)

so not enough light, too much debris.

[34:47] (2087.28s)

- To make matters worse.

[34:48] (2088.88s)

They could see that

about 10 years from now,

[34:51] (2091.20s)

they would need a new

generation of machine, a high

[34:54] (2094.24s)

NA EUV machine, essentially one

[34:56] (2096.40s)

with a larger optic system

[34:58] (2098.08s)

that could print smaller features.

[35:00] (2100.00s)

So what did they do?

[35:02] (2102.08s)

They decided to double down

[35:03] (2103.92s)

and invest in the next generation

[35:06] (2106.32s)

before they even got

the current one to work.

[35:08] (2108.64s)

- The most doubtful period

was in the beginning.

[35:11] (2111.20s)

So I started to work on this in 2012.

[35:14] (2114.08s)

By that time EUV was not working

[35:16] (2116.56s)

and there was this crazy

idiot working on the next

[35:20] (2120.32s)

generation where we could

not even make the EUV

[35:24] (2124.32s)

light in the first place.

[35:25] (2125.24s)

- Not only are you all in on

EUV, you're doubling down even

[35:28] (2128.72s)

before you know if EUV is gonna work.

[35:30] (2130.48s)

- Yes. - But to keep funding the

development, they needed money

[35:34] (2134.32s)

and lots of it.

[35:35] (2135.68s)

So they turned to the very,

who needed this technology

[35:38] (2138.80s)

- ASML reached out to its main customers.

[35:42] (2142.08s)

Okay, you want this technology

[35:44] (2144.56s)

for the next generation of chips?

[35:46] (2146.48s)

Well, you need to make

us able to invest more

[35:50] (2150.24s)

by investing in us.

[35:51] (2151.80s)

- Intel invested around

$4.1 billion and Samsung

[35:56] (2156.08s)

and TSMC in invested another

1.3 billion combined.

[36:00] (2160.08s)

So they can keep the research going,

[36:02] (2162.00s)

but with no product

[36:03] (2163.36s)

to show customers were

running out of patience.

[36:05] (2165.92s)

- We were crucified at every conference

[36:09] (2169.44s)

that the promises we

made last year we we were

[36:12] (2172.32s)

unable to live up to.

[36:13] (2173.76s)

Yeah. And they said, this is

what you showed two years ago.

[36:16] (2176.00s)

This is what you showed last year

[36:17] (2177.12s)

and this is what you're

telling me this year.

[36:18] (2178.64s)

So why would I believe you?

[36:19] (2179.92s)

- They were getting desperate.

[36:21] (2181.64s)

- But this was, I think about 2012 or

[36:25] (2185.76s)

or 13, we were struggling

to get the EUV power up

[36:29] (2189.52s)

and Kenoshita visited us.

[36:31] (2191.20s)

I took him to dinner

in a small town nearby

[36:33] (2193.68s)

and across from the

restaurant was a Maria Chapel.

[36:37] (2197.44s)

And now you know, science, we have come

[36:39] (2199.84s)

to the limits of science.

[36:41] (2201.44s)

Hey, let's go for divine intervention.

[36:43] (2203.36s)

So we went to the chapel so Kenoshita just

[36:46] (2206.40s)

to be safe lit three candles

for the three suppliers

[36:50] (2210.40s)

that were pursuing EUV

technology at the time.

[36:53] (2213.04s)

And lo and behold,

[36:54] (2214.72s)

and I have the data to prove it,

[36:56] (2216.48s)

there is a very strong correlation

[36:58] (2218.40s)

between us lighting the candle.

[37:00] (2220.56s)

- Okay. - And power going up.

[37:03] (2223.84s)

It's not causal effect, but

there is a strong correlation.

[37:07] (2227.00s)

- The big idea was instead

of hitting the droplet once,

[37:10] (2230.24s)

hit it twice,

[37:11] (2231.16s)

- One shot to hit the droplet

[37:14] (2234.00s)

and it expands in like a pancake shape.

[37:16] (2236.56s)

- Yep.

- And then only then have the second shot,

[37:19] (2239.84s)

the more powerful main pulse

where you evaporate the pancake

[37:23] (2243.76s)

and turn it into a plasma.

[37:25] (2245.36s)

This was a major breakthrough

[37:27] (2247.12s)

- By changing the target

from a droplet to a pancake.

[37:30] (2250.48s)

You got a larger surface area

for the laser to vaporize,

[37:33] (2253.68s)

but without the cost of adding

more debris or neutral atoms,

[37:37] (2257.20s)

because now the tin is

vaporized all at once.

[37:40] (2260.64s)

By 2014, they finally managed to hit

[37:43] (2263.44s)

that coveted 100 watts mark.

[37:45] (2265.68s)

But improvements in multi patterning

[37:47] (2267.52s)

with 193 nanometers now meant

[37:49] (2269.84s)

that EUV would only be useful

if the source reached at least

[37:53] (2273.36s)

200 watts and made 125 wafers per hour.

[37:56] (2276.52s)

- The source went from a hundred to 200,

[37:58] (2278.64s)

but as the industry moved

on, nobody waits for you.

[38:01] (2281.20s)

You know, they find other

solutions. We had to catch up.

[38:04] (2284.88s)

So it was a moving goalpost.

[38:06] (2286.40s)

- One of the problems was

how do you perfectly time the

[38:09] (2289.36s)

laser so you hit each of these droplets.

[38:11] (2291.68s)

- So the, the analogy is

a bit like a golf ball

[38:14] (2294.80s)

that you need to land in

the hole 200 meters away,

[38:18] (2298.96s)

not like laying on the green, not bouncing

[38:20] (2300.64s)

and getting the hole, but like

land in the hole every time.

[38:23] (2303.60s)

That's the level of precision

that we need to deliver the droplets.

[38:26] (2306.76s)

Those droplets are traveling through this like maelstrom of hydrogen flow.

[38:30] (2310.72s)

The speeds are tremendously

high, like shoot golf balls

[38:33] (2313.52s)

through a tornado and then

right when it lands at the hole,

[38:36] (2316.80s)

that's when it needs to

get hit by the laser.

[38:38] (2318.48s)

So in order to basically

track the droplets for that,

[38:41] (2321.60s)

we use laser curtains

[38:43] (2323.12s)

and we can sort of look

at when does the droplet

[38:45] (2325.44s)

pass through a laser curtain.

[38:46] (2326.64s)

Those scattered photons

tell us basically when

[38:49] (2329.28s)

and where is the droplet.

[38:50] (2330.80s)

And then importantly tells

us when to fire the laser.

[38:53] (2333.12s)

So we actually have to take into account

[38:54] (2334.80s)

how long will it take for the

light pulse to hit the droplet

[38:57] (2337.52s)

after we send the pulse.

[38:59] (2339.52s)

- Now by 2015, they were getting closer

[39:02] (2342.40s)

and closer to that coveted

200 watt mark when all

[39:05] (2345.92s)

of a sudden the ASML board

members got summoned.

[39:09] (2349.24s)

- This was one of these decisive moments

[39:11] (2351.92s)

where our customers were really

thin on patience and Martin

[39:15] (2355.76s)

and all the board members

were summoned to Korea

[39:18] (2358.40s)

to show 200 watt and they

were really fed up with it.

[39:22] (2362.40s)

You know, you either show

it now or you you go away.

[39:26] (2366.48s)

And when they entered the plane,

[39:27] (2367.92s)

the experiment was still running.

[39:30] (2370.00s)

- Okay? - When they exited the plane,

[39:32] (2372.64s)

they had the first result

demonstrating to all about,

[39:35] (2375.36s)

this is how close we came

[39:36] (2376.56s)

- With the source power up,

[39:38] (2378.24s)

there was one final problem

that had to be solved

[39:41] (2381.36s)

before they could begin

manufacturing their machine.

[39:44] (2384.24s)

See, while the hydrogen gas did

protect the collector mirror

[39:47] (2387.12s)

from debris, it wasn't perfect.

[39:49] (2389.68s)

All the intense high energy photons

[39:51] (2391.84s)

and hydrogen ions zipping around,

[39:54] (2394.00s)

deteriorated a very special

top coating on the collector.

[39:57] (2397.92s)

So they still had to clean

the mirrors every 10 hours,

[40:01] (2401.36s)

which you know is

terrible for productivity.

[40:04] (2404.00s)

Martin van den Brink asked

[40:05] (2405.12s)

for updates every day on their progress.

[40:07] (2407.44s)

But then one of the engineers noticed

[40:09] (2409.28s)

that every time they

opened up the machine,

[40:11] (2411.68s)

the mirrors suddenly seemed cleaner

[40:13] (2413.92s)

- Then he kind of chimed in

and said, oh wait a second.

[40:18] (2418.08s)

Whenever we opened up the

machine, oxygen comes in

[40:21] (2421.28s)

and our problem is solved.

[40:22] (2422.88s)

Couldn't we think of a way

to add just a little oxygen

[40:26] (2426.32s)

to our system and make sure

[40:28] (2428.24s)

that the collector stays clean longer?

[40:31] (2431.36s)

And so they started experimenting

with the amount of oxygen

[40:35] (2435.60s)

that was needed in the vacuum

[40:37] (2437.68s)

and then finally got to

this point, okay, if we add

[40:40] (2440.08s)

so much oxygen, we'll keep the

collector clean for longer.

[40:42] (2442.96s)

- With this fix ASML's

machine could run continuously

[40:46] (2446.32s)

for much longer and it finally

became commercially viable.

[40:50] (2450.64s)

By 2016, orders started pouring in

[40:53] (2453.12s)

and now all of the most advanced

chips need ASML's machine

[40:56] (2456.96s)

making them perhaps

the most important tech

[40:59] (2459.44s)

company in the world.

[41:01] (2461.04s)

ASML's first commercial machines

had a numerical aperture

[41:04] (2464.00s)

of 0.33 and could print

13 nanometer lines.

[41:08] (2468.00s)

These are called the low NA machines

[41:10] (2470.08s)

and a ML still makes them.

[41:11] (2471.84s)

But the machine that Jan's

team started working on back in

[41:14] (2474.80s)

2012 was the next generation

which had a larger optic system

[41:18] (2478.88s)

so they could print even smaller features.

[41:21] (2481.20s)

This is the high NA machine

with a numerical aperture

[41:24] (2484.40s)

of 0.55, and we get to see

their latest version up close.

[41:29] (2489.60s)

- How much is the machine?

[41:32] (2492.00s)

We always say north of 350 million euros.

[41:35] (2495.84s)

And you can actually buy it, right?

[41:37] (2497.28s)

You can if you want yeah.

[41:38] (2498.40s)

- If I had the money I could buy it.

[41:40] (2500.32s)

Yes you could.

- How many people have seen this before?

[41:43] (2503.32s)

- We really limit the amount of people

[41:45] (2505.76s)

- That get to go inside the clean room.

[41:47] (2507.68s)

ASML's machines are built in

a super strict clean room in

[41:51] (2511.12s)

any cubic meter, there can

be no more than 10 particles,

[41:53] (2513.84s)

only 0.1 microns large, and

nothing bigger than that.

[41:57] (2517.36s)

A spec of pollen is around 20 microns

[41:59] (2519.52s)

and extremely fine sand

is around 10 microns.

[42:02] (2522.64s)

To put all of this in perspective,

hospital operating rooms,

[42:05] (2525.68s)

which have to be extremely

clean, only allow a maximum

[42:08] (2528.88s)

of 10,000 particles per cubic meter

[42:10] (2530.96s)

that are 0.1 microns wide.

[42:13] (2533.76s)

It's so unfair

[42:14] (2534.88s)

how much better Marc looks

though in his white suit.

[42:18] (2538.32s)

I feel like a little smurf.

[42:21] (2541.28s)

- Okay, so we're gonna go

through the air showers,

[42:24] (2544.64s)

so you're gonna have to do as I do.

[42:26] (2546.80s)

- Okay, so this is washing down all the

[42:29] (2549.28s)

particles that are still on us.

[42:30] (2550.32s)

- Yes. So this is like

super clean air blowing

[42:32] (2552.88s)

as clean.

- This place is huge.

[42:36] (2556.26s)

- It's huge.

- It's insane.

[42:38] (2558.08s)

I've been in a clean room

a couple times before,

[42:40] (2560.72s)

but it's nothing compared to this.

[42:42] (2562.48s)

Are there any secret areas here

[42:44] (2564.32s)

where almost no one has access to?

[42:46] (2566.44s)

- I can't tell you.

- Great answer.

[42:50] (2570.00s)

- Okay. So this is the total system.

[42:52] (2572.08s)

- This is it. That's crazy.

Look how big it is.

[42:57] (2577.84s)

This is the most advanced

machine humanity's ever built.

[43:01] (2581.28s)

It's taken many, many years,

decades of development,

[43:04] (2584.96s)

many billions of dollars all

to get this humongous beauty.

[43:10] (2590.08s)

So this is the first high NA machine. - Yes.

[43:12] (2592.44s)

So if you saw pictures on

the internet or whatever.

[43:16] (2596.24s)

- Yeah.

- That's this machine.

[43:17] (2597.76s)

So the very first line's ever printed at

[43:19] (2599.76s)

eight nanometers and stuff.

[43:21] (2601.28s)

That was this machine.

- The smoothest object on earth.

[43:24] (2604.64s)

- Yeah, it's all in here.

- Yeah.

[43:26] (2606.12s)

- Wait, so let me see if I

can figure this out. - Yeah.

[43:29] (2609.28s)

- This is the light source.

[43:31] (2611.76s)

It's where they make the

extreme ultraviolet. - Yes.

[43:35] (2615.44s)

And then the laser must

come in from there.

[43:37] (2617.92s)

- Let's take a look at the laser.

[43:39] (2619.60s)

In fact, we got to see just

[43:40] (2620.88s)

how the laser and light source work.

[43:43] (2623.04s)

I think we're entering the

laser system here Mark's just

[43:45] (2625.92s)

making sure, I think that

we can actually film here

[43:48] (2628.00s)

that we're not catching anything.

[43:49] (2629.44s)

We're not supposed to. Oh

wow. This looks dangerous.

[43:53] (2633.52s)

Now the laser system is covered by all

[43:55] (2635.36s)

of these brown cabinets,

but here is a model version.

[43:58] (2638.48s)

A carbon dioxide laser

[43:59] (2639.76s)

of just a few watts enters

this amplifier where it bounces

[44:03] (2643.28s)

around until it's roughly

five times its original power.

[44:06] (2646.56s)

It then goes through a total

of four different amplifiers

[44:09] (2649.44s)

to bring the final laser

up to 20,000 watts,

[44:12] (2652.72s)

which is four times stronger than

[44:14] (2654.32s)

lasers that cut through steel.

[44:15] (2655.92s)

- Over here we have the amplifiers. - Yeah.

[44:19] (2659.04s)

That generates this. This

powerful laser beam. - Yeah.

[44:22] (2662.00s)

- And then it basically comes out

[44:23] (2663.76s)

and this is part of the

beam transport system.

[44:26] (2666.32s)

Where it's brought

to the machine.

[44:29] (2669.12s)

So this pipe here has

the big laser beam.

[44:31] (2671.92s)

- And this has a mirror?

[44:33] (2673.68s)

- Yes. - Then the pulses travel

to the light source module.

[44:36] (2676.96s)

It kind of looks like a transformer

[44:38] (2678.64s)

or like a, I don't know, like a spaceship.

[44:41] (2681.52s)

There's so many wires going

everywhere. - Don't touch this.

[44:47] (2687.48s)

- Holy crap. - This is pretty

big, huh? - This is insane.

[44:52] (2692.48s)

- And this is just a light source?

[44:53] (2693.84s)

- This is just a light source.

[44:54] (2694.96s)